Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice.

In conclusion, SDM is the preferred approach particularly relevant for preference-sensitive decisions. It is likely to lead to better professional-patient relationships, better decisions and better outcomes. Patients, becoming increasingly assertive, prefer this approach. It has been advocated for ethical reasons for over 40 years but nevertheless, is still not widely implemented in clinical practice. 1

In 2015, Stiggelbout, Pieterse and De Haes published an overview of the then current state of Shared Decision Making (SDM). The article begins with a nice description of the ethical and practical reasons for adopting shared decision making as the standard practice for preference-sensitive healthcare decisions. After documenting growing professional acceptance of the concept, the authors discuss why shared decision making was infrequently being used in clinical practice. They suggest that the problem could be due to varying interpretations of what shared decision making in clinical practice means, as documented in two prior papers, one by Makoul & Clayman 2 and the other by Moumjid 3. (For a summary and discussion of the Makoul & Clayman paper see the August 23, 2022 post)

“Despite professionals indicating that they consider it important to share decisions with patients …, SDM seems to be applied in daily practice to a limited extent only …. Several steps have to be taken before one can truly speak of SDM … and apparently people hold conflicting views on what these steps entail.”

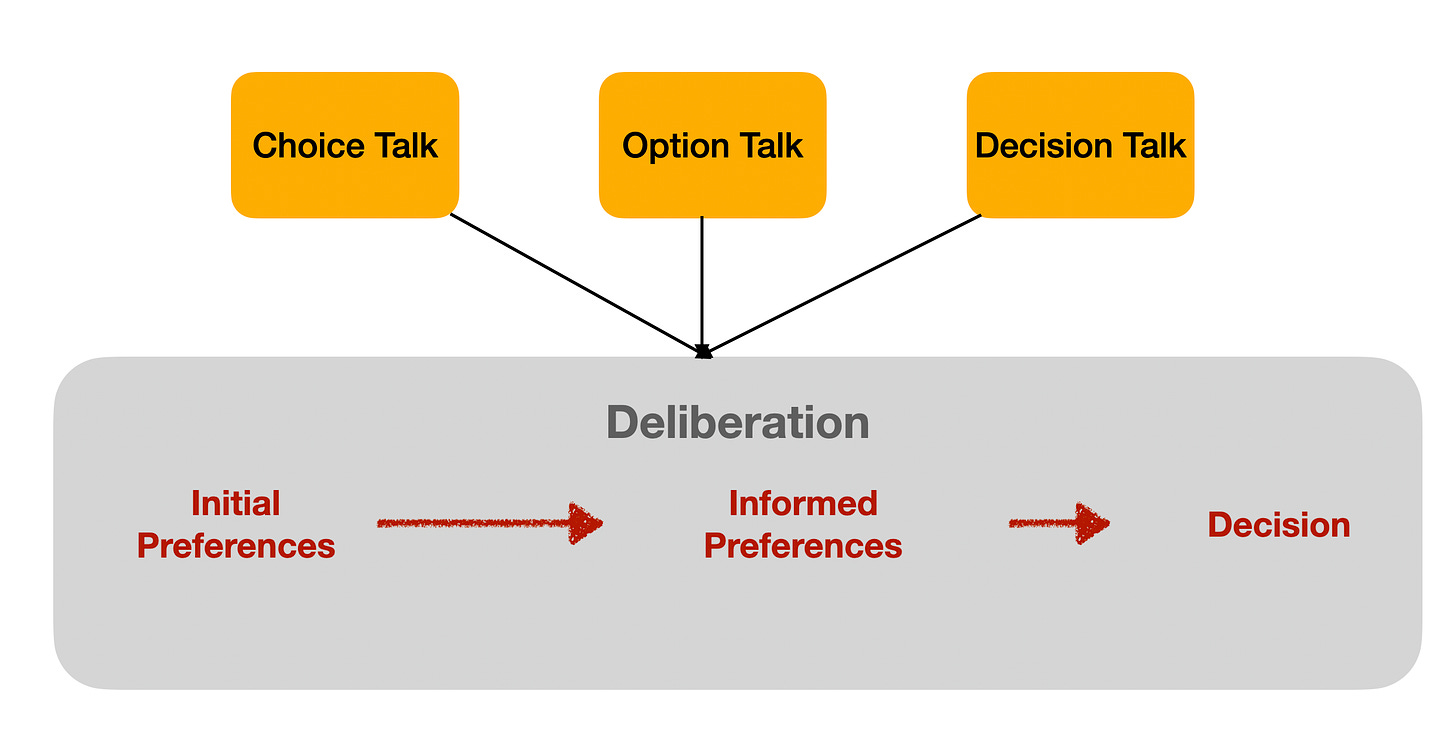

After summarizing the elements of shared decision making defined by Makoul & Clayman, the authors note that efforts had been underway to simplify the shared decision making process to make it easier to implement, most notably the 3-talk model discussed in the August 27, 2022 post. They propose adding a fourth step to the 3-talk model by dividing the decision talk phase into two separate components:

1. The professional informs the patient that a decision is to be made and that the patient’s opinion is important;

2. The professional explains the options and the pros and cons of each relevant option

3. The professional and patient discuss the patient’s preferences; the professional supports the patient in deliberation

4. The professional and patient discuss patient’s decisional role preference, make or defer the decision, and discuss possible follow-up.

To encourage implementation, they then present a series of conversational scripts and checklists that could be used to implement each step of their model during a clinical encounter.

Of note, the authors suggest that the discussion of who should be the primary decision maker, i.e., the individual who selects which option to pursue, be delayed until the fourth and final step in the process, after the decision scenario has been described and discussed. This is to ensure the patient has enough information to understand why their preferences are important before deciding whether they feel comfortable making the decision.

Stiggelbout and colleagues then review the existing information about how often each of the SDM steps is implemented in clinical practice and report that the answer for all steps was infrequently, if at all. They conclude: “The concept is simple, but … not easily implemented” and suggest several ways to to improve the implementation of shared decision making in clinical practice, primarily through the development of appropriate knowledge, attitudes, and skills among practitioners though the necessary knowledge, attitudes, and skills are not further specified.

Musings

Like the original 3-talk model, this proposal assumes that a high quality decision making process can occur through a process of enhanced communication. (It is worth noting that the article is based on a talk delivered at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the European Association for Communication in Health.)

I realize that the premise underlying a communication-based SDM model is that it will be easier to implement because it is consistent with the usual way clinicians interact with patients. However, similarity to usual practice could be a weakness rather than a strength if a communication-only strategy is easy to implement but not adequate to get the job done.

Einstein has been quoted as saying “Make things as simple as possible, but no simpler.” 4 I wonder if relying exclusively on inter-personal communication to implement shared decision making for complex healthcare decisions that depend on unbiased, well-informed, preference-based tradeoffs is trying to make things too simple to be effective.

The paper raises the question of whether shared decision making means the patient must always be the primary decision maker. My understanding is that the authors propose that shared decision making can occur even if the provider makes the final choice as long as the patient is actively involved in the decision making process and their priorities and preferences are factored into the decision. This appears to be another significant but unheralded modification of the originally proposed 3-talk model where the patient is the primary decision maker.

The paper does a good job of reviewing the existing evidence as of 2014 about how often SDM occurs in practice and the difficulties involved in collecting this information. I am always curious about which practices choose to participate in clinical decision making research. In my experience, many are not. Unfortunately, the authors do not include information about how practice sites were chosen for the studies they review. I suspect that the data on SDM for practices that had not been studied are likely to be worse than those that were studied.

1 Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015 Oct 1;98(10):1172-9.

2 G. Makoul, M.L. Clayman, An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters, Patient Educ. Couns. 60 (2006) 301–312.

3 N. Moumjid, A. Gafni, A. Brémond, M.O. Carrère, Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing, Med. Decis.Making. 27 (2007) 539–546.

4 There is evidence that Louis Zukofsky also should have some credit for this quote, see https://quoteinvestigator.com/2011/05/13/einstein-simple/.